The Lower Salem Creek Watershed here in Winston-Salem has significant water quality issues primarily due to fecal pollution. This pollution is primarily a result of increased urban development and run-off pollution. Lower Salem Creek directly discharges into Salem Lake. Both Salem Lake and Salem Creek, are classified as “headwaters of the Yadkin River and High Rock Lake,” and have significant water quality implications for Winston-Salem’s drinking waters. The City’s Storm Water National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (“NPDES”) permit is intended to protect the public drinking water, but there are currently not enough funds to take the necessary steps to manage runoff entering the Lower Salem Creek Watershed. Storm water utility fees could be used to fund projects and land conservation plans to protect the watershed and effectively manage polluted runoff.

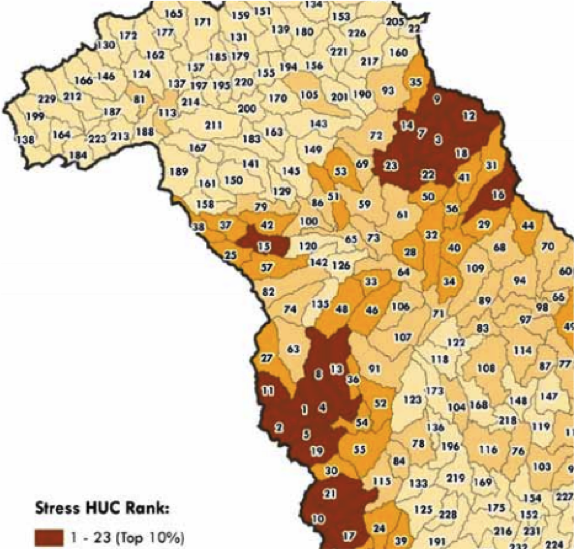

The water quality in this shed is a recognized problem. The North Carolina Department of Environmental and Natural Resources (“NCDENR”) ranked the drinking water source provided by Salem Lake has having high contaminant and susceptibility levels. In the following map, the Lower Salem Creek Watershed is labeled as number three, and is ranked as the third watershed in the Yadkin Basin for susceptibility to stressors and pollution.

On a more positive note, local watershed planning can address this problem. Specifically, if local support is taken the pollution and susceptibility levels in 10,622 of 35,472 stream miles with the Yadkin Pee-Dee river basin, including the Lower Salem Creek Watershed, could be efficiently addressed. The city of Winston Salem has drafted an action plan to improve this watershed’s water quality, that not only is a reservoir source for drinking water, but an area considered a hidden gem of Winston Salem.

The city has drafted a Master Plan involving a Water Quality Recovery Plan (“WQRP”) to address these toxic levels of fecal pollutants. This plan has identified methods the city can use to monitor and rectify the quantity and quality of storm water. First, the City recognizes that land use is critical to water quality. Continued urbanization has caused an increase in impervious surfaces. This has eliminated a filtration system usually provided by the natural environment. Furthermore, impervious land allows a greater volume of polluted runoff to enter watersheds in a shorter amount of time. Storm water utility fees could be used towards land conservation programs to ensure land located near and around the watershed is undeveloped. This would ensure the watershed has a natural filtration system that would prevent the need to install costly drain pipes and reconstruct the currently insufficient sewer systems.

Second, the types of activities taking place on land have significant effects on water quality. Industrial land use increases heavy metals and toxic substances, while agricultural use creates suspended solids such as fecal matter. Storm water utility fees could be used to develop a land use database that would in turn be used to devise a land use scheme. This would enable the city to understand what land use activity should be avoided, and where certain types of land use would be most effective to rectifying certain pollution levels in the watershed. Fees could also be used to ensure lands identified as critical for watershed protection would be protected from detrimental activity.

Third, the City’s Master Plan identified methods to provide an economically feasible land use model. This model would prevent the need to relocate and construct water and sewer lines that are currently not economically feasible. Storm water utility fees could be used to develop a model the City has identified that would be capable of “computing runoff, analyzing sanitary and storm sewer networks, and modeling treatment of pollutants.”

The City found a potential storm water program required the involvement of several city departments, and there was not enough funding to support the overall program. Directing storm water utility fees towards a storm water program could create a unified platform for watershed protection.

Using such funds would enable different departments to receive specific funding for projects directed toward watershed protection. No longer would activities and land use that affect water quality in the watershed be specific to activities within various city departments. They would be connected and analyzed as part of a unified funding scheme working towards improving water quality in the Lower Salem Creek Watershed.

Winston Salem has the ability to pursue such a plan, especially with support and friendly pressure from the public. If you are interested in turning your land into a land conservation trust or pursuing any land protection strategies, here are a two websites that can help you start your research, in addition to the Yadkin Riverkeeper!

The Conservation Trust of North Carolina: http://www.ctnc.org/

Piedmont Land Conservatory: http://www.piedmontland.org/

About the author : Alison Ringwood is a third year law student at Wake Forest University and a Masters in Sustainability candidate, graduating Spring 2016.